The patient, a young woman, arrived in the emergency department with a hip fracture sustained in an auto accident. As doctors and nurses worked furiously to address her physical injuries, a second-year Wake Forest PA student uncovered something about the patient that nobody knew.

“The auto accident was actually a suicide attempt,” said PA program director Sue Reich, recalling the story a former student had told her. “She was depressed after her boyfriend left her. She had never revealed it to anyone.”

The information the student was able to gather by asking probing questions of the patient led the ED team to get a mental health specialist involved. “It may have saved her life,” said Reich.

In the hectic environment of a busy ED, there is little time to ascertain such detailed information from a patient. But the student was working under the tutelage of a preceptor and had both the time and the curiosity to learn as much as he could.

It’s a story Reich said she’ll never forget, partially because of its dramatic nature, but mostly because it illustrates the symbiotic relationship between PA students and preceptors.

“Preceptors give PA students the opportunity to be hands-on with real patients and to practice what they’ve learned in the classroom,” she said. “But students can also help preceptors, their practices and their patients.”

Patients are the Real Teachers

The way Reich sees it, preceptors aren’t teachers in the traditional sense of the word. “They’re not there to spoon-feed students what they need to know,” she said. “They’re most effective when they’re the facilitators of learning.”

The real teachers, she continued, are the patients.

The real teachers, she continued, are the patients.

“As a preceptor, the best thing you can do is give students access to patients,” she said. When students gain access to patients in such a wide variety of clinical environments, from emergency care to obstetrics to gynecology, it’s an invaluable learning experience.

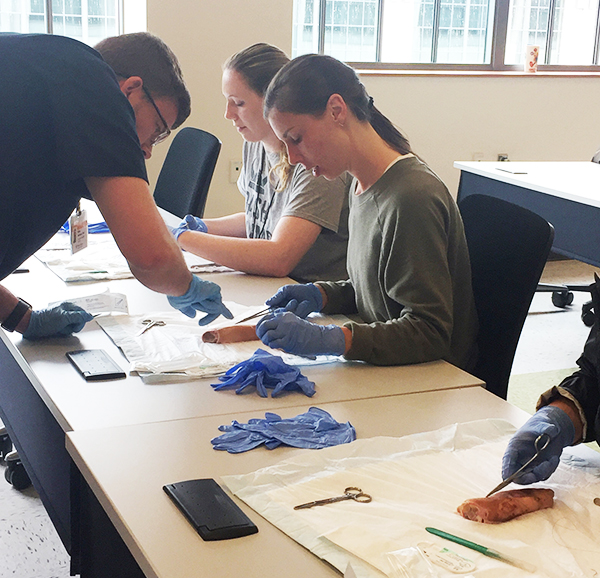

“It’s the opportunity to do real-world, hands-on work with actual patients,” she continued. “Taking histories, doing physical exams, documenting patient encounters, even assisting with minor procedures.”

Those experiences are critical to learning and developing the skills to ultimately practice medicine. It wouldn’t happen without access to patients. “Preceptors are the ones who allow this kind of learning to happen,” Reich said.

Armed with Curiosity

Students enter their year of clinical rotations after an intense didactic year. According to Reich, that didactic year prepares the students with one key trait: Curiosity.

“When a patient comes into a clinic, the main concern of the staff is to treat that patient’s symptoms,” she said. “Students have an opportunity to dig deeper and learn more.”

Armed with their curiosity, PA students are able to spend more time with patients and ask questions, not just of the patients, but of the preceptors, doctors and nurses. “They will look into the patient’s medications and learn why they were prescribed. They can ask the patient about previous clinical visits.

“Every patient presents an opportunity to gain knowledge, and the student is there to soak it up.”

Sometimes, that curiosity can serve to improve the patient experience, or even save a life, as it did with the woman with the fractured hip. But students can help the preceptor’s practice in other ways.

Preceptors often put students to work to improve the overall workflow and efficiency of their practices. “Students can check with the nursing station on patient progress, run down CT scans, and take patient histories,” said Reich. “So they can bird-dog things for the preceptors.”

Precepting Just Takes Patients

While students clearly offer preceptors and their clinics benefits in patient care and office efficiency, potential preceptors are sometimes hesitant to take on students, according to Lori Cook, program coordinator of clinical education for the Wake Forest PA program.

“They might worry about their ability to teach,” said Cook.

Cook’s answer to that concern is that they most certainly do have that ability within them. “A lot of potential preceptors think they need to be the kind of preceptor they had when they were students,” she said. “They think they have to spend an hour with the students every day, discussing each patient and telling students what they need to know.”

That approach has changed, Cook added, saying that the inquiry-based learning the students experience in their didactic year prepares them to take charge of their own learning. Students don’t need to see every patient, nor do they get in the way of things. If anything, they help.

“We can also work with preceptors to prepare them,” Cook continued. “We have tools and resources we can share to help them be great teachers.”

But the most important thing preceptors can do, again, is provide access to their patients. “That’s really where the learning happens,” said Cook.

Preceptors are Always Needed

Both Cook and Reich encourage anyone practicing medicine – doctors, nurses, and especially PAs – to consider becoming a preceptor. “Every PA has had preceptors to help them get to where they are,” added Cook. “This is a great way to give back to your profession and help the next generation.”

The Wake Forest PA program is always looking for preceptors in every specialty, but especially in women’s health, pediatrics, and family medicine. If you would like to know more about becoming a preceptor, contact Gayle Bodner, the director of clinical educationu.