The Wake Forest Journal of Science and Medicine is run entirely by students who believe in promoting relevant discoveries in clinical or lab science, medical cases, and perspectives on healthcare to the larger scientific community. We aim to educate students about the importance of an objective and rigorous peer-review process and to uphold the established Principles of Transparency and Best Practice in Scholarly Publishing.

Summer 2021 Articles

| Arab Muslim Refugee Women's Health Initiatives | Critical Pedagogy to Increase Diversity in Healthcare Professions |

| The Influence of Recipient Age on Outcomes Following Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation |

National Trends in Inpatient Diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury |

| Prognostic Factors in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

A Longitudinal Ultrasound Curriculum Improves Skill Acquisition |

| Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection in COVID-19 Patient | Hypocalcemia Presenting as a Code Stroke |

| Clinically Significant Progression of Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome |

Intentional Use of Carbapenem to Treat Valproic Acid Overdose |

| Product Use-Associated Lung Injury |

Thirteen Syndrome |

| An Atypical Presentation of NMOSD in a Young Adult with Visual Hallucinations |

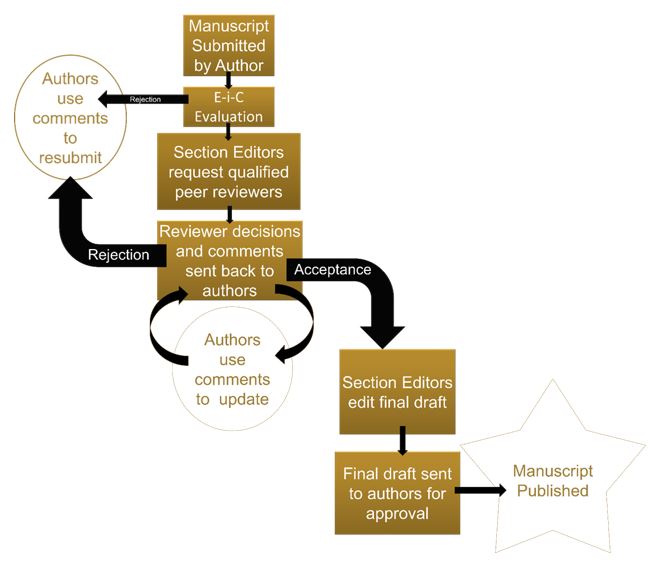

All manuscripts will be assessed by editors and may undergo a peer-review process. Manuscripts will be evaluated for scientific accuracy.

Editorial decisions will be

- Reject with review

- Reject or accept with revision

- Accept

A manuscript may undergo several rounds of revision before acceptance. Decisions will be communicated to the corresponding author via email.

Peer Review Flowchart

All submissions will be checked for plagiarism. The WFJSM uses the definition of plagiarism written by Dr. Miguel Roig for the DHHS Office of Research Integrity. Plagiarism is therein defined as: “Appropriating an idea (e.g., an explanation, a theory, a conclusion, a hypothesis, a metaphor) in whole or in part, or with superficial modifications without giving credit to its originator... Copying a portion of text from another source without giving credit to its author and without enclosing the borrowed text in quotation marks… Self-plagiarism occurs when authors reuse their own previously written work or data in a ‘new’ written product without letting the reader know that this material has appeared elsewhere.” - http://ori.hhs.gov/images/ddblock/plagiarism.pdf.

Corrections and Retractions

Since the Wake Forest Journal of Science and Medicine is released annually, there is ample time for corrections before print publication and every effort will be made to ensure that errors are caught in the editing process. In regards to honest errors that are found after publication, the Wake Forest Journal of Science and Medicine will follow the ICMJE’S guidelines for corrections. Corrected versions of manuscripts will be electronically published with the previous version archived. Pervasive errors that invalidate previous results may lead to replacement of the manuscript altogether. Citations will be linked to the newest manuscript.

Misconduct

The Wake Forest Journal of Science and Medicine agrees with the ICMJE’s definition of misconduct as including but not limited to data fabrication, data falsification including deceptive manipulation of images, purposeful failure to disclose conflicts of interest, and plagiarism. In regards to misconduct, staff will follow procedures delineated by the COPE flowcharts. Manuscripts submitted by authors who have knowingly engaged in misconduct will not be reviewed for publishing. Manuscripts that have already been published will be labelled as ‘retracted’ online with an explanation for the retraction.

Authors are responsible for obtaining written permissions to republish or reproduce any previously published material from the copyright holder of the original source. The authors of manuscripts contained in the WFJSM grant WFJSM exclusive worldwide first publication rights and further grant a nonexclusive license for other uses of the manuscripts for the duration of their copyright in all languages, throughout the world, in all media. Copyright ownership of these articles remains with the authors. Authors may be asked to complete and sign a copyright form.

Authors must refrain from submitting work which they have published or hope to publish elsewhere. This practice will ensure that authors' works meet the ICMJE's standards regarding overlapping publications.