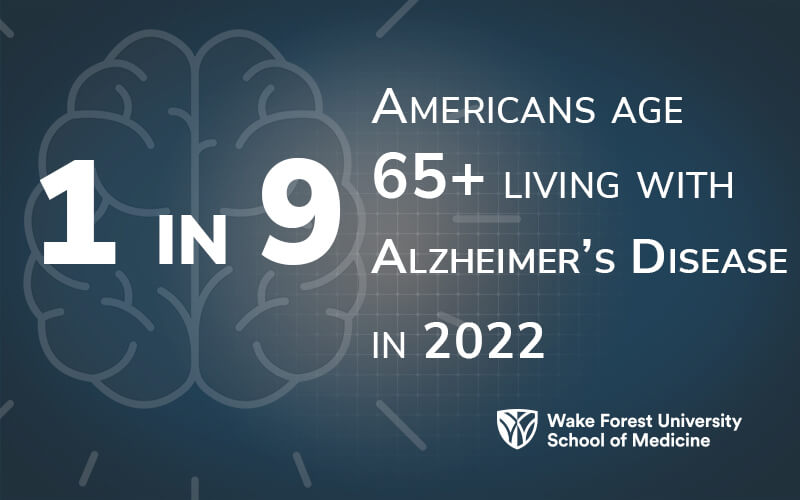

Alzheimer’s disease, one of the costliest illnesses in the U.S. and one of the top 5 causes of death for Americans 65 and older, currently has no cure, very few treatments and no way to reliably predict who is at increased risk for developing it. The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at Wake Forest University School of Medicine is approaching that enigma in multiple ways, including:

- Developing a screening tool that could be applied easily in a primary care setting within approximately two years.

- Examining metabolic and immune markers in blood and cerebrospinal fluid to try and understand some root mechanisms that cause Alzheimer's.

- Expanding participation of research study participants and of investigators, trainees and students at the center.

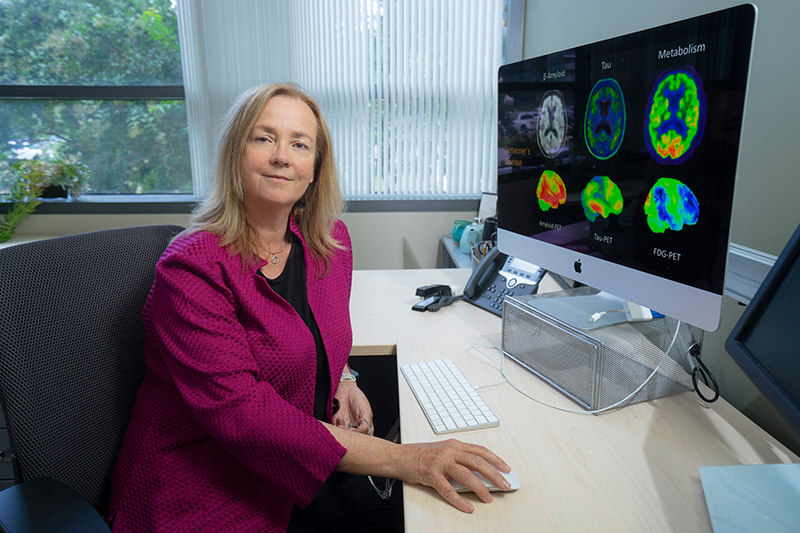

“We want to care for those who have advanced dementia and their caregivers, but we are also very focused on trying to identify risk and very early disease so we can have a meaningful intervention that slows progression and gives people good years of high-quality life,” said Suzanne Craft, PhD, director of the center and professor of gerontology and geriatric medicine at the School of Medicine. “And we’re starting to be able to do that with very accessible means.”

The Wake Forest ADRC has been at the forefront of finding early interventions to slow or halt the progression of Alzheimer’s since it was established in 2016. Because of this success, in 2021 the National Institute of Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, awarded a second cycle of funding, $15.2 million over five years. One goal for this five-year cycle is to better characterize risk factors for Alzheimer's and examine whether addressing those risks can be a useful way to reduce the chances of getting Alzheimer’s or to delay the onset.

An Algorithm for Early Identification

Because of the long lag between the start of Alzheimer's pathology in the brain and when a person starts showing symptoms of Alzheimer’s, knowing who to screen, what to screen for and when to screen is a major challenge. Michelle Mielke, PhD, chair and professor of epidemiology and prevention, said Wake Forest’s ADRC is working to develop an algorithm that will detect early change in cognition to better predict cognitive impairment. The next step would be to extrapolate this algorithm across the multitude of health care systems and medical records systems in the U.S. and around the world.

|

“We want to develop a system that can be used easily and efficiently in primary care, that can more quickly identify people who might need to be monitored every year or two, and then, if a change in memory and thinking skills is detected, we can get on to their treatment much sooner. We want to have our health system ready so that when a new treatment is available, we know exactly who will benefit from it.” - Jeff Williamson, MD, MHS, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. |

To develop the algorithm, researchers will recruit approximately 1,000 diverse participants over a year and evaluate health factors including:

- Comorbidities

- Frailty index

- Medications (number and type)

- Social determinants of health

- Demographics

- Changes in behavior

The Alzheimer's risk detection algorithm will develop and refine the profile of patients for a doctor or other health care provider to recommend for further screening. Such screening might include using artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze speech, as well as blood tests that assess specific Alzheimer's biomarkers, which is another area of investigation for the center.

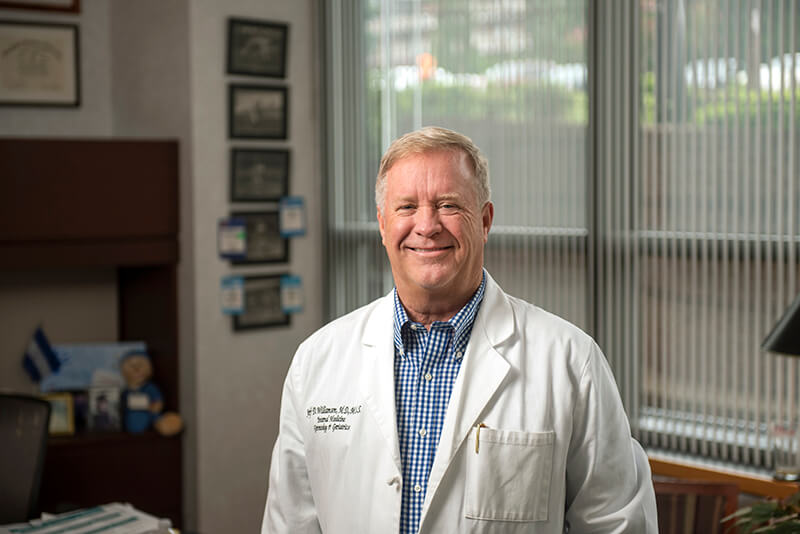

Jeff Williamson, MD, MHS, associate director of the ADRC and section chief and professor of gerontology and geriatric medicine, said a screening tool will help physicians know which patients should receive follow-up testing. Because not everyone needs to be screened, an Alzheimer's screening test would be recommended for specific persons in higher risk groups, much like mammograms screen women over a certain age or with a family history of cancer.

“We want to develop a system that can be used easily and efficiently in primary care, that can more quickly identify people who might need to be monitored every year or two, and then, if a change in memory and thinking skills is detected, we can get on to their treatment much sooner,” Williamson said. “We also want to have our health system ready so that when a new treatment is available, we know exactly who will benefit from it.”

Craft and Mielke pointed out that early detection provides a better chance to slow progression or, possibly, reverse certain symptoms. And the Wake Forest ADRC has multiple studies that focus on ways to intervene through healthy diets, exercise programs or controlling blood pressure or blood sugar.

Mielke, who came to the School of Medicine in April 2022, said Wake Forest is very well known for its work in nonpharmacologic interventions. It is the coordinating center for U.S. Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk (U.S. POINTER), the leading study examining whether lifestyle interventions that simultaneously target many risk factors protect cognitive function in older adults who are at increased risk for cognitive decline. Laura Baker, PhD, associate director of the ADRC and professor of gerontology and geriatric medicine, leads the study. Under the direction of Williamson, the School of Medicine also led the nationwide Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial Memory and cognition in Decreased Hypertension (SPRINT-MIND) study that demonstrated for the first time that better blood pressure control can prevent memory decline.

“Part of our research is to continue to investigate accessible ways, accessible interventions that give people an extra layer of cognitive protection,” Baker said. “My job is to find how we can give people more resilience, one more layer of protection, so they have a little more time or they have a little bit more resilience against disease.”

Combining that kind of work with early screening and assessing genetic risk leads to a precision medicine method of Alzheimer’s intervention.

“It’s absolutely not one size fits all,” said Craft. “It’s your special risk profile that we can identify and help develop a strategy for reducing each of the risk factors that are salient for a given patient.”

Multiple Tools Means Greater Precision

Much like prior research that has shown increased cholesterol or blood glucose indicate future risk for heart disease, Mielke works on blood-based biomarkers to predict future Alzheimer's risk as part of the center’s neuropathology core. She said there is a huge push to add that type of testing as a supplemental screening or diagnostic tool. A blood test would give physicians a flexible option to gather biologic information, especially for patients who can’t undergo imaging or lumbar punctures, and provide broader access to rural populations and places that don’t have the infrastructure to do scans or other expensive, high-tech testing.

However, Mielke points out there remains much work to be done in establishing cut points and understanding how to interpret the markers at the community level, where the population is more diverse and has more comorbidities. In fact, Mielke was part of the group that developed recommendations for the use of such biomarkers in clinical and research settings for the Alzheimer’s Association.

Another important mechanism for determining who might develop Alzheimer’s is deciphering a person’s genetic risk. Craft wants to recruit an expert in polygenic risk to develop methods of assessing an individual’s genetic risk profile. Because Alzheimer’s is almost certainly caused by having several genetic risk alleles, small genes contributing small amounts and additive risk, knowing a person’s polygenic risk score could make a significant difference in that person’s clinical care.

“That’s something we hope to offer patients,” Craft said. “That we will be able to tell them what their polygenic risk scores are and if the risk is in a range that should be considered a potential problematic level, and what we can do to address the genetic risks for the various components.”

Building Translational Bridges

Craft thinks Wake Forest’s ADRC will become leaders in using the precision medicine approach to treating Alzheimer’s disease within five years, in part through leveraging the academic learning health system created by the School of Medicine and Atrium Health. Williamson concurs.

“As an academic learning health system, we’re going to be positioned to help the people who come to us preserve their independence, cognitively and physically,” Williamson said. “Alzheimer’s is the end-stage brain disease, and my hope is that 15 years from now, there’ll be very few people who even reach that level.”

“This disease is personal to all of us,” Baker said. “We've all worked with the patients so intensely for so many years that they're just part of our family. And we care about these families and we really want to find a way to help them, and that's kind of what drives us all."